Today’s seed drills are a feat of sophisticated engineering and a vital tool of modern farming; but who was the man behind the first seed drill and how did his invention change farming forever?

Today, the idea of agriculture without mechanisation is unthinkable. And yet there was – of course – a time when all farming was just that: the manual work of men alone, helped by tools no more advanced than the sickle, the scythe and the animal-drawn plough.

One of the first pioneers who did something to change all that – who introduced to farming, through a single ingenious invention, a revolutionary element of mechanised control – was Jethro Tull, deviser of the seed drill.

He was born in Berkshire in 1674 into a middle-class family of landowners.

Jethro Tull

The Tulls had worked hard over the generations to enlarge their estate – but precariously so, and without avoiding debts and lawsuits along the way. Though they owned more than one property, the future of neither the estate at Howbery in Oxfordshire nor that of Prosperous Farm on the Berkshire / Wiltshire border could be taken for granted.

This uncertainty may have affected the course of Jethro’s life from an early age. We don’t know for sure why he gave up a fledgling legal career (having read law at Oxford and been called to the bar in London when he was just 19); but we do know that by his mid-twenties he was back home in the country, married (to the daughter of a well-to-do Warwickshire family) and pouring all his energies into improving the efficiency of his father’s estate.

Out of these energies came the discovery that would make his name.

Frustrated by the meagre returns of one of the family farms, Tull resolved to give the whole of it over to growing sainfoin – then a highly favoured crop. But he worked out, from his observations in the field, that for sainfoin to flourish profitably, the seeds were going to have to be sown more deeply and more widely spaced than was the custom of the time.

And the custom of the time was entrenched. Tull was faced with the task of persuading his farmhands – who prided themselves on being ‘prime seedsmen’ – to set aside their centuries-old plough-and-scatter tradition in favour of sowing the new seeds sparingly, into specially dug furrows, and at properly calculated intervals.

What happened next was a spark of class conflict that started up the engine of historical change. As Tull tells it, his men were ‘jealous that if a great quantity of land should be taken from the plough it would prove a diminution of their power’. They refused to cooperate, Tull was ‘forced to dismiss’ them and an entirely new way of sowing the sainfoin had to be found.

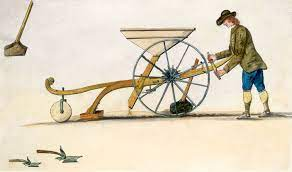

Thus Tull set about constructing a specially-made field ‘drill’; and he came up with a machine – a sort of plough with built-in seed hopper – that would plant seeds to the depth and density he needed by dropping small quantities of them at periodic intervals behind the furrowing blade.

The idea of sowing seeds from a moving seed box was not original to Tull. Such things are known to have existed in ancient China and India; and at the beginning of the seventeenth century an Italian implement was described, at the time, as resembling a kind of ‘flour sieve’ on wheels.

What was new with Tull’s design was the rotary seed release mechanism. Modelled, in fact, on the way in which the soundboard in a church organ lets air into organ pipes, Tull’s seed drill controlled the release of seeds from the seed box by means of notches in the revolving axle underneath – with mechanical precision and regularity.

‘My drill,’ Tull would later recall, ‘planted that farm better than hands could have done and many more hundreds of acres than the hands could have done besides.’

At some point in his life (possibly in the course of his agricultural experiments) Tull became seriously ill with lung disease – so seriously, that he went to live, for two years, in the south of France. And there he found not just recuperation but fresh inspiration.

It was while visiting the vineyards of the region that Tull was struck by how the vines were nurtured to maturity: not through the application of manure, but by a constant hoeing of the soil around the plants as they grew. Conscious that, courtesy of his seed drill, his own fields were now also planted in neat, widely spaced rows, Tull was impatient to see if he could reproduce some of the vineyards’ success with English farm crops.

This, once back home, he did; and in so doing became an advocate of the practice of continuous tillage.

Though Tull’s understanding of the science was incomplete (and on at least one count wrong: he thought that the roots of plants absorbed minuscule particles of soil as food), he was nevertheless able to demonstrate how beneficial it was to protect crops from the competition of weeds, while maintaining a soil aerated and free from the problems of compaction.

Innovative new designs for horse-drawn hoes followed and were published, alongside Tull’s own summation of his life’s work and discoveries, in The New Horse-Hoeing Husbandry (1731).

The book remained controversial throughout its several early editions. Its stance against the use of manure was particularly castigated (though also exaggerated: the slogan popularly attributed to Tull – ‘tillage is manure’ – he seems never actually to have said).

By the time of his death, at the age of 66, in 1741, Tull’s ideas and innovations were being discussed and debated in every corner of the agricultural establishment.

The man himself, when he looked back on his career, knew that it was the seed drill that had started everything. He reflects in the preface to his book that, without it, and the new level of control it brought to the farmer’s interaction with both crop and field, his subsequent studies of seeds and soil would have been ‘impracticable’.

He reflects, too – with modesty, perhaps – on how ‘accidentally’ his invention had been ‘discovered’; and, wisely, on the unpredictable dynamics of progress, by which the least likely things ‘may unexpectedly become useful’.